Unkept promises on flucytosine

EU research funds for helping people living with HIV in Africa so far appear to have only helped Sanofi’s profits

This article is an updated version of a case study contained in the report "More Private than Public – The ways Big Pharma dominates the Innovative Medicines Initiative" (IMI), part of our series “In the Name of Innovation – Industry controls billions in EU research funding, de-prioritises the public interest”.

The Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) is a large-scale public-private partnership – with €2.6 billion of public money – between the European Commission and the pharmaceutical industry lobby group EFPIA (European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations). While its stated aim is to “improve health by speeding up the development of, and patient access to, innovative medicines”, IMI embodies a model by which the public sector foots a large part of the bill, while the private sector is able to set the pharmaceutical research agenda in its own interests - and reap the rewards.

So when IMI says the results of one of its research projects – CHEM21, which received almost € 10 million in EU public research funding – is “expected to decrease drastically costs of production” of an anti-fungal drug, flucytosine, “and so make the medicine more affordable for the many people with HIV/AIDS who live in low income countries,” it’s worth digging deeper. Because so far, while a pharmaceutical corporation seems to control key parts of the intellectual property for the process resulting from this IMI project, a process that enables the cheaper production of other, more profitable drugs, flucytosine is not being manufactured with it and remains out of reach for millions of people living with HIV/AIDS.

The first public-private partnership, IMI, ran from 2008-2013, and was renewed as IMI2 to run from 2014-2020. IMI is up for renewal again in 2020, with plans to shift its focus to digital health. One of the projects funded by IMI, “Chemical Manufacturing Methods for the 21st Century Pharmaceutical Industries” (CHEM21), is a project focusing on making “the drug development process more environmentally friendly,” which it claims will “help the pharmaceutical industry to cut costs, resulting in cheaper medicines for patients”. CHEM21, which ended in June 2017, was coordinated by the pharmaceutical company GSK and ran several projects including the development of a “new, more efficient way” of producing a drug known as flucytosine.

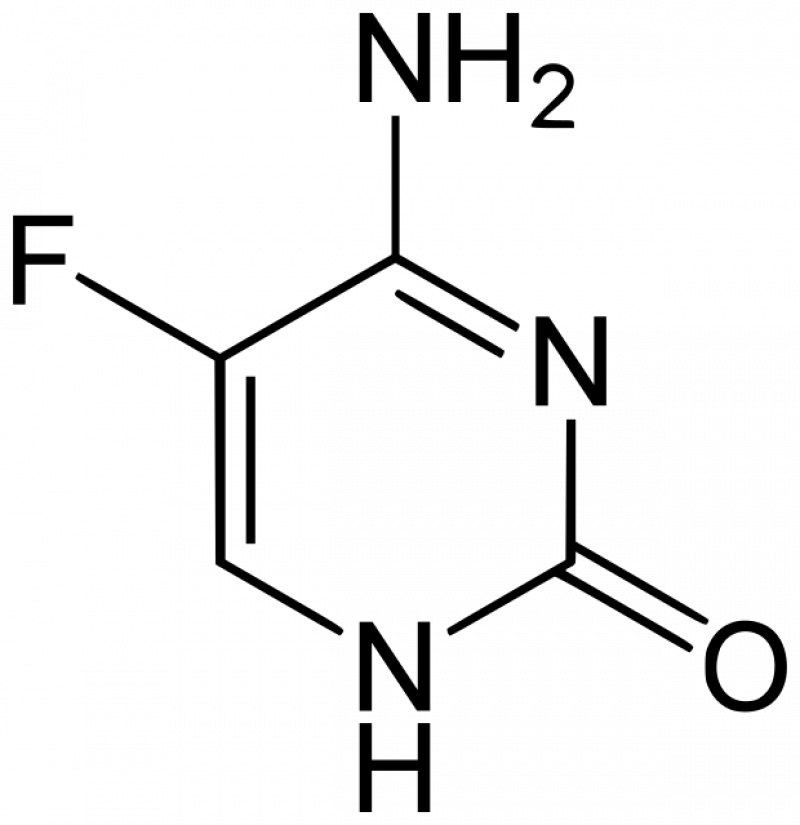

Flucytosine is a 60 year old medicine, and was once used for cancer treatment but it is also a critical anti-fungal medicine for the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis, one of the main causes of death among people with HIV. An estimated 181,000 AIDS deaths each year are due to cryptococcal meningitis, and medical NGO MSF states that combining flucytosine with other drugs “could cut cryptococcal meningitis death rates from 70 per cent in low income countries to less than half”. Flucytosine is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, which lists the safest and most effective medicines for health systems.

However, flucytosine is not available in most of Asia and Africa. In sub-Saharan Africa, where flucytosine is largely absent, the death rate is much as 70 per cent, a figure comparable to Ebola: as one reporter puts it “where the need is greatest, flucytosine remains entirely out of reach”. A 2013 Lancet article on access to cryptococcal meningitis treatments noted that “the main barriers to access to flucytosine include absence of drug registration and generic drug manufacturing in low-income and middle-income countries.

MSF has been campaigning for registration of affordable flucytosine for several years (the registration of medicines is “the process by which a national regulatory authority approves the use of a medicine in a country, having considered evidence of the mMedicine’s safety, quality and efficacy. It is thus primarily concerned with protecting public health”). They argue similarly that “pharmaceutical corporations have not registered the treatment in high-burden countries that are not able to pay the exorbitant prices charged by US corporations”. Indeed, while the medicine has been for sale on the global market for over 60 years, the price has significantly gone up in recent years. While a decade ago the product was for sale in the US for $6 per day, in mid-2018, the product was for sale in the US at a price of $2000 per day, 100 times more expensive than in Europe.

While a generic version of flucytosine has been approved, generic pharmaceutical company Mylan obtained the license in 2016 and, according to MSF, “promptly doubled the price”. The generic price of flucytosine is approximately US$120 for a week-long course, and while be significantly lower than the previous on-patent price, MSF points out that flucytosine is still “unaffordable and unavailable to most people in need” and has urged the company to “prioritize its registration more broadly in low- and middle-income countries".

Thus one of the activities of IMI’s CHEM21 project was to design a new, “more environmentally friendly” production method that would “drastically decrease” the manufacturing costs of flucytosine, explicitly stating that this would “make the medicine more affordable for the many people with HIV / AIDS who live in low income countries”.

In theory this is a valuable endeavour, all the more so given that the new production process also produces less pharmaceutical waste. The key participants in the project were the University of Durham, which originally developed and patented the new process (and received €152.5053 from the EU under CHEM21), and pharmaceutical company and EFPIA member Sanofi.

Sanofi contracted out French group MEPI (Maison Européenne des Procédés Innovants) to develop a commercial-scale version of the process to produce the drug, which was successfully achieved by early 2017 (the proven production rate was 1kg per day but the authors stated that their approach could easily be upscaled by a factor 30 to 50).

Pierre Meulien, the Executive Director of IMI, said: “This is an excellent example of how through IMI, universities and pharmaceutical companies can work together to deliver a promising discovery that addresses an unmet medical need, and then rapidly progress it to a larger scale.”

Except the “rapid progress” seems to have slowed to a halt after the project ended. Neither Sanofi nor any company seem to have started manufacturing flucytosine with this new method. According to sources familiar with the project, Sanofi is now controlling the intellectual property (IP) for the upscaled manufacturing process and is likely to have entered into an IP transfer agreement with Durham about the original process. Sanofi did not respond to our repeated questions to clarify this (nor to new questions sent before the publication of this case study) and Durham refused to comment on this point, citing confidentiality issues.

The University told us that “Durham owns some of the IP arising out of the project, which we have patented but not yet licensed. We are active in looking for ways to ensure this technology is used. We have been in discussion with a number of potential licensees in a number of sectors. [Durham also told CEO in February 2020 that to their knowledge the pharmaceutical company Mylan, the main manufacturer of the drug today, was not among these]. We are interested in using this technology for both commercial and social responsibility purposes (for example in low and middle income countries).”

Two years later, a Sanofi factsheet merely notes that a technology transfer “would be proposed” to the South African company Inicio/Pelchem, which specialises in fluor-based compounds thanks to abundant local resources (Fluor gas is a precursor to flucytosine in this process). Yet we could not find any evidence that discussions between these two companies even started (neither of the two companies replied to our questions).

What happened?

For the University of Durham, this was part of a longer-term project on the use of the application of fluorine gas in industry, and is touted as one of their “successful knowledge transfer partnerships with industry”. A Durham professor and his research group even received the 2018 AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Pfizer and Syngenta Prize for Process Chemistry Research for this project on behalf of the Durham Fluorine Group, an award given to “chemistry that has the potential to be of relevance to large scale manufacturing”.

Universities make a significant amount of their income from the transfer or sale of licenses to industry to commercialise the results of their research. Public health NGOs advocate for universities to implement ‘socially responsible licensing’ to ensure that such knowledge transfers come with conditions to ensure access to the results, especially for low income countries. Durham however does not appear to have a policy of using socially equitable licensing, nor the European Commission requires or encourages the use of it or other forms of public-interest driven licensing as a condition for IMI or any other EU biomedical R&I projects (with the exception of a latest call for COVID-19 projects – not for medicines or vaccines though - issued on 19 May 2020 under the EU research programme Horizon 2020, which includes "an obligation to license on a non-exclusive basis and at fair and reasonable conditions").

The CHEM21 project page notes that the patented process, with its efficiency gains and potential cost-savings, can also be applied to capecitabine, an off-patent cancer drug which Sanofi does sell, and emtricitabine, a commonly used HIV treatment also sold by Sanofi in one of its drugs, brand name Atripla. This raises the question of whether this project – advertised as rescuing the poor – will one day result in any additional supply of affordable flucytosine? In particular whether it will – as IMI claimed – help put the drug in reach for people living with HIV/AIDS in low-income countries? Or whether instead it has merely provided Sanofi with a handy – and publicly-funded – cheaper process in the production of two of its existing medicines?

Meanwhile, people with HIV/AIDS keep dying in Africa for lack of access to flucytosine. International global health organisations like UNITAID are trying to help by buying the drug from generic manufacturers. And MSF’s campaign to push Mylan to register flucytosine in African countries seems at least to have delivered some results: according to an email they sent CEO in February 2020, Mylan has just moved the manufacturing site to India to reduce flucytosine production costs, and finally filed to register the medicine in South Africa in December 2019 and with WHO Pre-Qualification(PQ). It took time, but thanks to public pressure, and not the new production method developed by CHEM21 with EU funding, things seem to be finally moving a bit in the right direction. But will Mylan also register flucytosine in more, and lower income, African countries?

A couple of observations can already be made.

First of all, necessary safeguards – which ought to have been set by IMI – would have been needed to ensure that any lower production costs are reflected in a drop in the price of the end product. Otherwise, the efficiency gains obtained with public funding only end up boosting the profits of the company owning the rights. The IMI project does not spell out how efficiency gains in production cost will translate into lower prices for patients and healthcare systems.

It is unlikely that the IMI successor, to be called “European Partnership for Health Innovation” will put in place the much-needed safeguards for affordability and accessibility given that, according to IMI internal documents obtained by Global Health Advocates, the pharmaceutical trade association and lobby group EFPIA is in the driving seat to write the agenda.

Second, increasing patient access to affordable flucytosine was a commendable goal. Yet IMI appears not to have sufficiently grasped the factors that hindered patient access to affordable flucytosine, such as the absence of drug registration and generic drug manufacturing in low-income and middle-income countries. Pfizer, another EFPIA member, after being submitted to strong public pressure, has been providing a related (but weaker) antifungal medicine for free to developing countries for many years. This suggests that companies can be pushed to prioritise the public interest where it is most needed… And that IMI is not a structure doing this.

Third, although this was a project run with taxpayers’ money it has been impossible to access key information about the fate of its results. The intellectual property has been privatised.

Meanwhile, this particular CHEM21 project – advertised as rescuing the poor – has not yet resulted in a supply of affordable drug for people living with HIV/AIDS in low income countries. But the results of this publicly funded project have already provided Sanofi with a cheaper way to produce two of its existing medicines. Asked by Politico Europe to comment on the findings of this investigation, an IMI spokesperson "acknowledged that there’s not much it can do if companies don’t follow through" and commented that “projects are not obliged to report to us in the long term after the end of the project," which made it "very hard to follow up on long-term impacts.”