Co-opting the COP

How the finance sector captured the UN climate finance agenda

Corporate Europe Observatory outlines the role the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) plays in the corporate capture of climate finance at the COP unfolded, and why they need to be stopped.

The role of finance has become a key issue at the climate summits (known as the Conference of the Parties COPs). The private financial sector stole the whole climate finance agenda at COP26, and the run-up to COP27 in Egypt is looking to be a repetition. The issue is crucial for several reasons. For one, the so-called developed world continues to shed its responsibility and refuses to find the money to pay for the transition in the Global South. Secondly, the financial sector’s massive funding of fossil fuel investments is a major obstacle to meaningful climate action. It is deeply troubling then, that the very investors funding pollution have been put in charge of handling how financial markets are regulated (or not) in the light of climate change. Their agenda of ‘self-regulation’ appears to be drowning out any of notion of rules agreed on and enforced by public authorities.

The development of this part of global climate policy started at COP21 in Paris, But the subject of tackling financial flows in order to address climate change was not dealt with in substance until the Glasgow COP26 in 2021. Unfortunately, those taking up the mantle were not governments, they were finance corporations with huge vested interests in the issue. Under the leadership of former Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney and Wall Street tycoon Mike Bloomberg, hundreds of financial institutions had joined ranks in the run-up to the conference, corporations convened by the UN to take charge of the private finance agenda. A full day at the COP was dedicated to climate finance; some of the most important financiers of fossil fuels were key protagonists.

Polluters left to decide

According to their less than reassuring vision, finance corporations can and will take care of the climate challenge through voluntary commitments to meet ‘’net zero by 2050”, a concept that leaves plenty of space for them to continue business as usual through eg offsets or carbon trading.

‘Net zero’ is an idea – perpetuated by Big Polluters – that their continued emissions can be ‘balanced’ by offsetting, capturing, or removing CO2. Changing the goalposts from real zero – which would involve actual emissions cuts starting with a rapid phase out of fossil fuels and a just and sustainable scaling-up of real renewable energies – to ‘net zero’ emissions is a sleight-of-hand boon to the fossil fuel industry and its financial investors.

It is unsurprising, then, that it was with messages about ‘net zero’, that finance corporations joined together to form the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), pushing the implicit message that little or no action is needed from governments. Finance corporations can handle it themselves. Yet there is nothing in their recent history that shows them changing significantly. Of the 60 banks that have invested a staggering US$3.8 trillion in fossil fuels since the Paris Agreement was signed, 40 are in the Net Zero Banking Alliance, one of 7 alliances that make up the GFANZ.

Indeed a quick look at the list of leaders of the GFANZ coalition, the so-called Group of Principals, reveals a large number of world famous financiers of pollution. There is Larry Fink from BlackRock, an asset manager famous for its deep involvement in the coal industry, and which is a laggard even on the weak net-zero targets. Or take Citi, one of the five US banks that dominate fossil fuel financing globally. Or take Standard Chartered, a bank that funds fossil fuel projects that emit five times the UK’s annual emissions.

This decision to go for self-regulation leaves us with a huge problem. There is no solution to the climate crisis without changes to financial markets. If big banks, investment funds, and asset managers can pour endless sums into the development of fossil fuel exploration and infrastructure without restriction, we are unlikely to be able to change the course away from more disastrous runaway climate change. To simply ‘let the market rule’ in this case would be suicidal. While the financial sector has an interest in steering clear of the risks posed by climate change to their own investments this is a fairly limited frame; in the bigger picture, they do not have the same incentive to care for the planet, and many (very profitable) reasons for not doing so. For that reason, the corporate capture we have seen at the UN on climate finance urgently needs to be stopped.

The Paris Agreement: what does it mean for finance?

It was the 2015 Paris Agreement that moved the matter of private finance up the political agenda with the introduction of wording on financial markets, marking an important and groundbreaking change to international climate policies. Article 2.1 c stipulates that going forward, efforts to fight climate change will include making “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate resilient development”.

While the wording of the article is not very precise, there is no doubt that it has transformative implications. A close analysis of 472 preparatory documents, tabled by governments before the Paris meeting, concludes that it cannot be understood merely as a pledge to mobilise support for the transition in the Global South. This is because it is not only about “provision of finance”, it inserts a “climate consistency goal” for all financial flows. All financial decisions have to be in line with a ‘pathway’ towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate resilient development. That should surely mean that financial investments must be consistent with the Paris goal of keeping global warming under 1.5ºC .

In another legal analysis from the UN Library of International Law, Professor Daniel Bodansky underlines that the article “goes well beyond the traditional focus of climate finance on the provision of support to developing countries”. He explains: “It encompasses private as well as public financial flows and calls not only for increasing green finance flows to support low emission technologies and climate resilience, but also for phasing out brown finance flows used to fund greenhouse gas emitting technologies (such as coal-fired power plants).”

What is the benchmark for financial reform?

From this, it follows that financial markets as well as public investments, must be transformed to underpin a global effort to keep the temperature from rising above 1.5ºC. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) as well as the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the benchmark, then, is simple.

A report from the International Panel on Climate Change concludes that projected cumulative future CO2 emissions “over the lifetime of existing and currently planned fossil fuel infrastructure without additional abatement exceed the total cumulative net CO2 emissions in pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C (>50%) with no or limited overshoot”. In other words, any investment in new fossil fuel infrastructure will take us above the target from the Paris Agreement.

On a related note, the IEA states in a report that if the pathway to keeping global temperature from rising above 1.5ºC is to be followed, there is “no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply”; they explain, “No new oil fields are necessary…. No new natural gas fields are needed… beyond those already under development.” In other words, any new fossil fuel project is in contradiction with the Paris Agreement. To some, that’s a given. But coming from the IEA, that’s news. “ This is huge,” Oil Change International said in a comment: “ An agency that has consistently boosted new oil and gas development in its flagship annual World Energy Outlook (WEO) is now backing up the global call to stop the expansion of fossil fuel extraction.”

Paris opened the door to business

Since Paris, though, little has been done to implement this article. While there have been frequent clashes over the lack of funds to fulfil the obligation of ‘developed countries’ to finance transition in ‘developing countries’ to the tune of US$100 billion annually, the broader – and even trickier – question of financial markets has been largely ignored.

But while little was discussed at the intergovernmental level, a decision in Paris to involve the private sector and other actors more directly in the implementation of the agreement has led to several initiatives in the years after Paris. Not least the so-called Marrakech Partnership, set up to build cooperation with business and civil society to “strengthen collaboration between governments and key stakeholders” to “enhance and accelerate climate action among Parties and non-Party stakeholders”, and which has had a major impact.

This ‘multi-stakeholderism’ of the Marrakech Partnership has so far defined the implementation of article 2.1. c in various ways, not least through the formation of platforms for ‘Net Zero’ reductions of emissions from various business sectors. Most importantly, the ‘Race to Zero Campaign’ has been set up to facilitate plans for emissions reductions from businesses, cities, regions, institutions, and businesses. The Race to Zero Campaign, then, provides guidelines to the various coalitions of businesses that have emerged in recent years, including GFANZ.

What risk are we talking about?

The financial sector has been on alert against the challenge of being ‘regulated’ due to climate change for years: in Paris in 2015, lobbyists from the finance sector were well organised and active. Both banks and insurance companies have large sums at stake. They have worked on models that will guide them in their attempts to save themselves, not the planet. As one high-ranking BlackRock executive stated: “In the financial services industry, when people talk about climate risks, they don’t mean risk to the planet; they mean risks to their portfolio…. We’re not trying to stop Miami from getting wrecked by climate change. We’re trying to get our money out before it hits.”

So, while it’s no wonder that the financial industry is keen on playing a role in addressing climate change, its models are largely based on its own fears of losing out in the short term, rather than a fear of destroying the planet in the medium term. At the COP it is crucial, then, that whatever is decided on climate finance, starts from the right point – the risk to people and ecosystems, not the financiers’ pockets – and that the finance sector is not allowed to take the initiative and impose formulas based on merely shielding their own interests. Unfortunately, at the UN level, the finance sector long ago started building up strongholds that have now allowed them to capture and dominate the agenda on private finance and climate change.

Building financial industry participation

In the case of the financial industry, COP26 was to be a breakthrough for the concept of ‘net zero’. Long before the Glasgow summit, a UN agency, the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI), started building coalitions of finance corporations that were prepared to sign up to commitments to reach “net zero by 2050”. Though formally a UN organisation, the UNEP FI is actually an invention of the financial industry, and it is largely run by their representatives. It was formed in 1992 at the initiative of a group of financial corporations, including Deutsche Bank, HSBC, NatWest, and many more.

The UNEP FI effort and that of the Race to Zero coalition, led to the formation of seven separate coalitions representing the various sections of the financial sector: the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance, the Net Zero Banking Alliance, the Net Zero Financial Service Providers Alliance, the Net Zero Investment Consultants Initiative, the Paris Aligned Investment Initiative, and the Net Zero Insurance Alliance. Due to the key role of the UNEP FI, they were all in a sense ‘UN-convened’, a fact they are all keen to highlight on any given occasion.

In parallel, two important personalities were moved into key positions to take these coalitions to another level. In December 2018, the UN Secretary General appointed Wall Street tycoon Mike Bloomberg as his Special Envoy on Climate Action, and in December 2019 the Secretary General appointed Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England and former Goldman Sachs Director, as his Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance. Only a month later, the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson appointed Carney as his finance adviser for COP26. And Carney was a good salesman for the cause. To his peers in the financial industry, he vowed that the transition ahead would prove to be “the greatest commercial opportunity of our time”.

On the basis of this groundwork, a coordinating body for the various coalitions was set up, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, GFANZ. Under the direction of a ‘Group of Principals’, the minimum commitment criteria of the Race to Zero Campaign are developed into tools and frameworks in order to ensure compliance from finance corporations.

COP26: a parade of big bankers on stage

GFANZ dominated the finance day at COP26, 10 November 2021. In fact, the big public event at the summit was organised by Mark Carney and his associates – with few government representatives around. On that occasion, Mark Carney made bold statements about the impact of the commitments made by the now 450 financial institutions that had signed up to the net zero coalitions. With these banks and investments funds on board, the funding for the transition was within reach, he claimed. And in the name of GFANZ, he had already presented a strategy – a document presented on the official COP26 website before the event itself.

In response the media reported a climate finance bonanza: “Banks and asset managers representing 40 percent of the world’s financial assets have now pledged to meet the goals set out in the Paris climate agreement”, Bloomberg wrote, while the New York Times reported: “Global Finance Industry says it has 130 trillion dollars to invest in efforts to tackle climate change”. They were, according to the article, “committing to use that capital to hit net zero emissions targets in their investments by 2050, in a push that would make limiting climate change a central focus of most major financial decisions for decades to come”. This was a very misleading take.

This was all presented as a dazzling culmination of the attempt to turn around financial markets: a block of financial corporations had taken matters into their own hands! With no governments playing a role, they would adjust their approaches to meet the targets with no regulatory intervention. And perhaps as a reflection of this corporate capture of the agenda on private finance, nothing in the main declaration from COP26 went further into the matter. Appreciation was expressed in the Glasgow Climate Pact for “commitments made to work together with non-Party stakeholders”, and a call was made for multilateral development banks “and other financial institutions” to “enhance finance mobilisation”. Climate finance was needed “from all sources to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement”, so action was welcomed to “unlock the potential to contribute” to the targets.

Net Zero – the less glittering reality behind the promises

In this way, the emergence of GFANZ means finance corporations have captured the agenda on private finance and climate change. And at a very small price. While Carney’s statement on the US$130 trillion was heralded as a bold promise to put an unimaginable fortune on the table to save the planet, what it was really about was something unimpressive: the sum is merely the total of investments under administration by the 450 financial corporations in the net zero coalitions. It does not mean they are to be reinvested to support a transition, merely that the institutions that control them, have committed to ‘net zero by 2050’.

‘Net zero’ is based on the concept that continued emissions can be ‘balanced’ by the removal of carbon from the atmosphere, through offsetting, capturing, or removing CO2, and it’s gained acceptance thanks to the lobbying of dirty energy giants. Fossil fuel companies that want a free pass to keep pumping oil and gas are making wildly unrealistic promises about 'capturing' their emissions at sites of pollution, or removing them from the atmosphere at later date. But the science says drastic emission cuts are needed now if we are to stay within 1.5ºC warming. Thus ‘net zero’ policies are in reality 'not zero', and effectively guarantee that we’ll overshoot 1.5ºC, triggering catastrophic climate impacts which we have no reason to believe can be reversed.

The trillions of dollars mentioned by Carney, then, is not money on the table. It is a vague prediction that the net zero commitments will at some point deliver big sums for the transition.

Yet, while the commitments vary from sector to sector, common to all are their fundamental flaws that render their actual impact highly questionable. The Net Zero Banking Alliance leaves it unclear what the associated banks need to do before 2030, whereas the Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance does not even operate with interim targets – all talk is of a very distant future with ‘net zero emissions by 2050’. Amazingly, the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative states that their investments should only be covered by obligations “to the extent possible”. These and other flaws are explained briefly in a briefing from CEO and TNI, and in more depth in a report from Reclaim Finance.

What is required by the Race to Zero Campaign?

What they have signed up to collectively through their membership of GFANZ, is the ‘net zero’ framework from the Race to Zero Campaign, elaborated to guide not only the GFANZ, but other industries as well. That too leaves a lot to be desired. The minimum requirements oblige companies to set an interim target by 2030 for them to take their “fair share” of emissions reductions, and to explain within 12 months what the following steps will be. This – crucially – is to be seen in the light of the emission cuts being ‘net zero’ which brings in a lot of possibilities to evade reduction at the source. Net zero opens the door to all sorts of loopholes, including purchasing of carbon credits, investments in dubious conservation projects, and so on.

The criteria of the Race to Zero Campaign were weak from the beginning, so weak in fact that there has been sufficient pressure for the campaign to adjust its course. While maintaining key characteristics, including the net zero approach, the criteria have been strengthened since COP26 in 2021. In June 2022, wording was introduced about fossil fuels for the first time, and the plans expected from companies were described in more detail. Also, new language was introduced: “Each Race to Zero member shall phase out its development, financing, and facilitation of new unabated fossil fuel assets, including coal, in line with appropriate global, science-based scenarios”. While the little word “unabated” creates flexibility and vagueness in the design – allowing for widespread reliance on technical fixes with little proven effect that allows the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels – this sentence may appear to make the Race to Zero Campaign somewhat less flawed. In fact, it leaves the financial industry with a major loophole they can exploit.

What can make the GFANZ change?

However, the strengthening of the RTZ criteria does not mean the GFANZ will adjust its course. In September 2022 16 civil society organisations denounced statements made by a UNEP FI official who said it is “unlikely" that individual alliances will need to update their core commitments to meet Race to Zero’s new rules”. And on 17 October, the chair of the Net Zero Banking Alliance Tracey McDermott of Standard Chartered, wrote a letter to its members to stress that the NZBA "has an autonomous governance structure and decision making process, which is set out in the Governance document. Any changes to the NZBA’s Guidelines can only take place in accordance with that governance." And the umbrella of the coalition, the GFANZ leadership, "cannot direct the NZBA or its members to act in any particular way," she said in her letter.

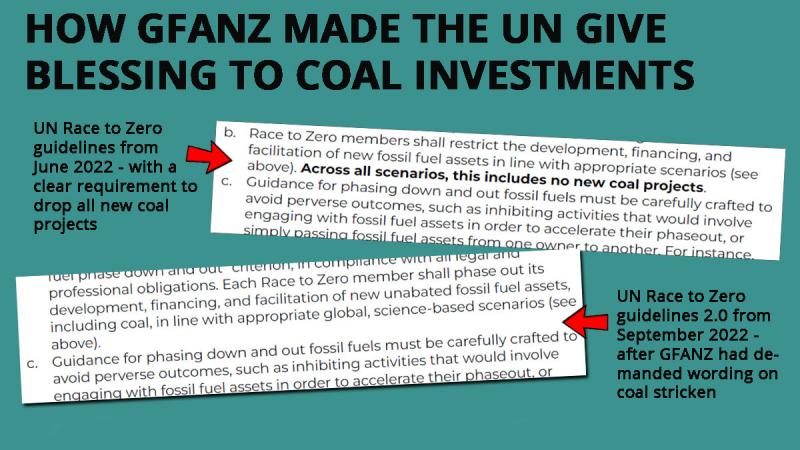

In fact, recent events show that GFANZ may have a bigger impact on the Race to Zero Campaign’s criteria than vice versa. When the recent version of the RTZ criteria were published in June 2022, they included clear wording on coal. A sentence stressing the need to restrict financing of new fossil fuel assets was followed by a clear requirement: “Across all scenarios, this includes no new coal projects”. But amazingly, after complaints from members of GFANZ, the RTZ campaign decided in September to strike the sentence.

This underlines another weakness in the whole Race to Net Zero setup: there are no enforcement mechanisms. The worst thing that can happen for a company that acts in clear contradiction with the criteria, is that said company is asked to leave the coalition. This is no real deterrent. And even then, the question is who can or will make that call. A show of solidarity from fellow bankers may hinder such an exclusion from happening.

To complete the picture, the GFANZ has now initiated its own internal discussion about the criteria, and has even completed a public consultation on its ideas for “Enhancements to Measuring Net-Zero Portfolio Alignment for Financial Institutions”. These show the GFANZ seeking a model that would require the least possible adjustments to their business models. “Climate solutions”, for instance, are presented in the main as a technical challenge which entails a speedy spread of new technologies. The 140 page report that serves as the basis for the consultation hardly mentions divestment nor fossil fuels.

Why do they resist so fiercely?

Hence there is no sign that the GFANZ will ever be serious about the energy transition when it affects the fundamentals of its members’ business models. And who can wonder. While there are financial institutions in their midst who have changed their portfolios profoundly over the years, that cannot be said for the majority, nor the biggest corporations in GFANZ. Except for Chinese banks, there is hardly a single major investor in fossil fuels on the planet that has not made it into the GFANZ coalition.

It is the heads of these companies that are to lead the GFANZ in these critical years when, according to the IPCC, emissions have to be cut by half by 2030 to avoid irreversible and even more disastrous climate change. Having big bankers and asset managers at the steering wheel, then, should be a cause for concern. Despite this, not only is the GFANZ not under critical pressure, on the contrary: the mandate of GFANZ is even expanding.

What are the implications for climate finance at the COP?

In the run-up to COP27 in Egypt, GFANZ seems to be taking on an even bigger role in the area of climate finance. The Egyptian hosts and people from the UNFCCC have organised a series of regional forums in Africa, Asia, and Latin America to discuss access to climate funding with governments. In all forums, the GFANZ is a co-organiser and participant. And what’s more, representatives from GFANZ are participating in the selection of projects that deserve to be taken forward.

Why should this role of GFANZ be of concern? Because even before COP26 Mark Carney presented its views on climate financing (in this case “mobilization” of finance) in the Global South. These are modelled on a view of the world often heard from financial corporations: for climate finance to reach the Global South, what is needed is for governments to introduce far-reaching investment protection, tax breaks, and generally for them to open their markets more to global capital. In essence, such a model would undermine local ownership of the transition – and it would more generally tilt the balance of power in the economy in the favour of global finance. This is the way forward, according to the Climate Finance Leadership Initiative, headed by Mike Bloomberg. An initiative whose platform was highlighted in the GFANZ strategy document prepared for COP26 by Mark Carney.

With this, the GFANZ is potentially expanding its reach into the broader climate finance agenda at the COP. It is about much more than changing (or not) their own portfolios – they are involved in a push to make developing countries offer them better conditions for their investments.

This should be seen in the light of ongoing talks at the COP level about the obligation of so-called developed countries to bear the biggest burden and provide funding for the transition. So far, they have only committed to US$100 billion annually, which is a very small sum considering the cost of the transition will definitely run into the trillions. And even that amount has not been reached. Still, with GFANZ it could become even worse, in that the US$100 billion are supposed to come from not only public sources, but private sources too. In other words, finance that reaches a developing country from private sources, for instance a project approved by GFANZ, could in principle be considered part of the developed world’s contribution and deducted from the total sum of transition funds.

Where should we go from here?

The GFANZ model for mobilisation of climate finance for the Global South really helps to complete the picture of how financial corporations capturing the agenda on private finance. With the GFANZ’ standing at the COPs, financial corporations are allowed to handle the transition themselves, and they do that on the basis of ‘net zero approaches’ that broadly speaking allow them – and the companies they invest in – to continue business as usual. And more, they are able to exploit their position to gain the upper hand with developing countries.

Considering the role in financing climate destruction played by many of these corporations, it is urgent to dethrone them and take away all privileges they now enjoy at the UN. Already there is a strong call for a Conflict-of-interest framework at the COP as well as calls to remove fossil fuel lobbyists from the COP altogether. That should apply to their financiers as well.

And on top of dealing with the power of the finance sector, there is a second step to take that is just as important. Governments need to drop the illusions about self-regulation. What is needed is for governments to develop credible rules on divestment from fossil fuels and put in place enforcement mechanisms to pave the way for a true transformation of financial