Toxic lobbying: the titanium dioxide label debate continues

For the past two years, in the anonymous committee rooms of the EU institutions, member states and Commission officials have been debating whether and how to regulate a chemical found in many everyday substances. You may not have heard of titanium dioxide, but check the list of ingredients in your toothpaste, sunscreen, or cosmetics, and you may well find it. The French Government, backed by the European Chemicals Agency, considers it to be a “suspected carcinogen” when inhaled, and today (1 July) the Commission and member state officials will once again meet to discuss how to handle this chemical. The classification of titanium dioxide by the EU as a “suspected carcinogen” would not lead to a ban, or even to restrictions on the chemical or its use, but would simply mean that products containing it need to be clearly labelled as potentially carcinogenic, to provide information to workers and consumers. This makes the clamour of industry lobbyists against classification especially shocking.

Titanium dioxide: the story so far

The World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has determined that titanium dioxide is a “possible carcinogen for humans”. In 2017 the French Government’s scientific assessment found that titanium dioxide is a carcinogen when it is inhaled. As a result of this finding, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) was charged with providing a recommendation to the European Commission on the matter. In its own assessment ECHA broadly supported France, but proposed classifying all forms of titanium dioxide as a “suspected carcinogen” (rather than an outright carcinogen) when inhaled. Since then, for the past two years, the Commission has been presenting proposals to the REACH comitology committee (consisting of officials from the 28 member states) in an attempt to find agreement on whether and how to classify the controversial chemical. Some member states, including those with a significant chemicals industry - Germany, Slovenia, and the UK among them - have made clear their opposition to the ECHA position that recommended classifying the chemical as a “suspected carcinogen”.

The latest Commission proposal to classify titanium dioxide contains a major loophole.

However, the latest Commission proposal to classify titanium dioxide contains a major loophole. While the pure powder form of titanium dioxide would be required to have a label which might say something like “Suspected of causing cancer by inhalation”, when the chemical is used in a liquid, or another kind of mixture (eg in paint, sunscreen, or toothpaste - very commonly used domestic products), it would only require a less serious label saying something such as “Warning! Hazardous respirable droplets may be formed when sprayed. Do not breathe spray or mist”. This is extremely worrying, as titanium dioxide is almost always used via mixtures. Thus, if this classification proposal were adopted, the vast majority of products used by consumers and workers would include only the weaker label, thereby failing to properly explain the health risks of titanium dioxide.

In response to this loophole, The Guardian has reported an EU source stating: “I am ashamed to say I don’t know why we are derogating them [exempting mixtures]. We should not be having a problem with this. I think it is because we received a lot of pressure from industry... It has been the worst I have seen... Without proper labelling, people may not wear masks when they are using spray paints, and they would be exposed.”

Intense industry lobbying

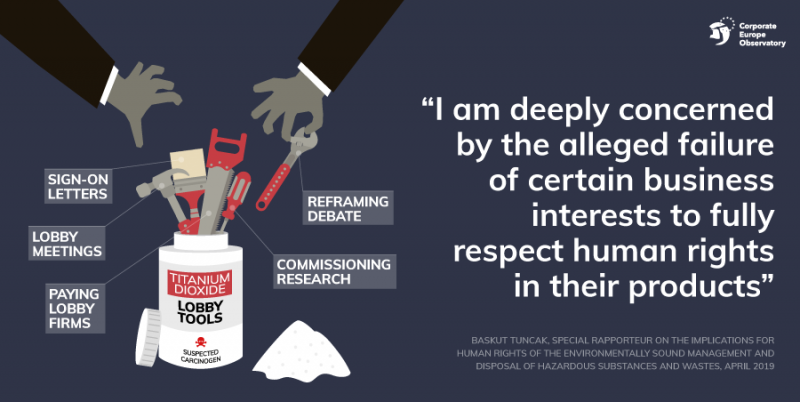

The scale of industry lobbying on this file has far outweighed the voices of NGOs and trade unions who have advocated for the public interest and raised issues of human health and a safe environment. Industry’s massive resources have enabled it to deliver repeated and coordinated lobby demands. Ranging from the Titanium Dioxide Manufacturers’ Association’s (TDMA) brag regarding its €14 million research programme to “build the scientific basis to help discuss and resolve the many issues that present themselves in the current, unique situation”; to numerous emails, letters and position papers sent to DGs GROW, Environment, and the Secretariat General; or sign-up letters coordinated within industry sectors; and of course lobby meetings and phone calls, industry has waged an intense and wide-ranging lobby battle.

Building on Corporate Europe Observatory’s earlier analysis of lobbying on this issue, from June 2018 to March 2019 the Commission (in the shape of DGs GROW, Environment, and the Secretariat General) documented at least 36 letters, emails, and meetings from or with industry, on the classification of this single chemical. This compares to only seven from trade unions and NGOs. SidenoteIncluding one from Corporate Europe Observatory, document 7 in this batch received under EU access to documents rules

Additionally, industry appears to be working hard to cover as many relevant lobby targets as possible. Member state governments have been a primary lobby focus, due to their key decision-making role on the REACH comitology committee (which has, up to now, been the main actor on this file). Further developing the picture of intensive lobbying we already documented in a previous report, in the eight months since July 2018 the TDMA has continued to lobby the UK Government, with five phone calls and a meeting with officials having been documented. If this pattern is even partly replicated across the other 27 member states it shows that industry is devoting significant resources to influence member states’ positioning. Le Monde has reported how, piling on the pressure further, when a member state official agreed to meet with industry to discuss titanium dioxide, no less than 24 people turned up.

Industry has also brought on board at least two lobby firms to help with its influencing campaign.

Industry has also brought on board at least two lobby firms to help with its influencing campaign. The chemical industry’s EU trade association CEFIC (which declares spending €12 million a year on EU lobbying, making it the EU’s largest lobby group) employs Fleishman-Hillard (Brussels’ largest lobby firm). According to LobbyFacts, Fleishman-Hillard has been paid at least €400,000 a year by CEFIC for activity on titanium dioxide, and examples of its work include a sign-up letter addressed to three Commissioners, sent on behalf of the producers of titanium dioxide and TDMA members. SidenoteDocument 2 in this batch

German lobby firm Alber & Geiger is also active on the titanium dioxide decision, on behalf of chemical producer Chemours, with this lobby firm soaking up over €300,000 of Chemours’ total declared lobby spend of €500,000+ per year. Alber & Geiger approached the Commission on behalf of Chemours, complaining of the “devastating market disruption” that would follow classification, and demanding a lobby meeting with officials. SidenoteDocuments 16, 16.1 and 17 in this batch The lobby firm lobbied a Cabinet member of Environment Commissioner Vella on titanium dioxide in September 2018.

The employment of these lobby firms is another indicator of the scale of the resources that industry has dedicated to opposing the classification of titanium dioxide.

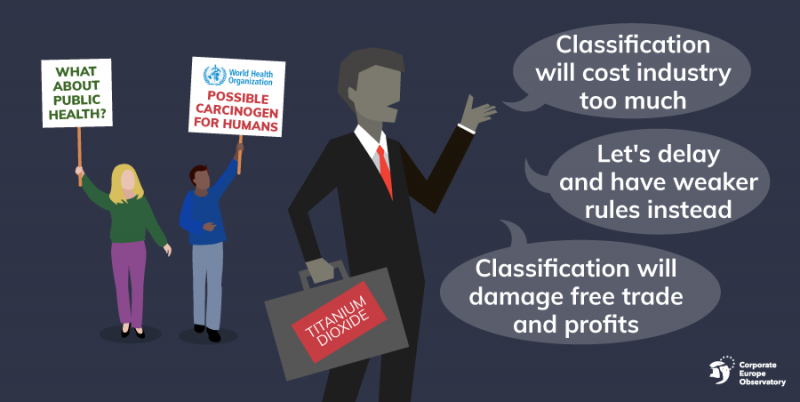

But even more striking than the scale of the industry campaign, are the arguments that business interests are using to undermine the classification of this chemical. Below we explore some of industry’s arguments, and its attempts to reframe the discussion in its own interest.

“We want ‘Better Regulation’”

The ‘Better Regulation’ agenda of the EU, as Corporate Europe Observatory has previously reported, is industry and Commission-speak for weakening and abolishing current rules to protect the environment, workers’ rights, or public health, while also hampering the introduction of new regulations. In the context of the classification of titanium dioxide, a key argument used by industry is that the decision-making process on the issue is in breach of the Commission’s so-called Better Regulation framework.

Industry body TDMA has exemplified this tactic, calling for “the available alternative regulatory options to be fully considered in line with the EU’s proportionality principle and Better Regulation Guidelines.” TDMA’s parent body CEFIC says something similar, and demands an impact assessment, SidenoteDocument 1 in this batch while industrial users of titanium dioxide (including the paint and inks industries) have backed these bodies’ positions. SidenotePages 13-14 in this batch

Unsurprisingly, the neutral-sounding impact assessment process would play right into the hands of industry. Decision-making on the classification and labelling of chemicals is supposed to only focus on the intrinsic potential of a chemical to pose harm, as determined scientifically. But, as Corporate Europe Observatory has noted elsewhere, impact assessments enable industry to introduce economic arguments into the discussion, such as costs to industry, while putting monetary values on the expected costs and benefits of a policy, which tend to privilege economic impacts over environmental and social ones. Additionally, if industry doesn’t like an impact assessment’s results, they often then dispute its methodology, to try to undermine it.

It is clear that industry’s attempts to shift this chemical classification procedure into the ‘Better Regulation’ and impact assessment process is an effort to buy more time and political space to oppose a classification that would likely put customers off its products, and thus in turn reduce its profits.

Waste-d arguments

As part of industry’s efforts to divert attention away from the hazard reasons for regulating titanium dioxide, business also complains that the ‘downstream’ costs of classification would be too high. This brings us to the issue of waste, with industry arguing that classifying titanium dioxide as a “suspected carcinogen” would lead to a lot of waste being newly classified as hazardous, thus making it ineligible for recycling and reuse within the circular economy, and in turn more costly to treat and dispose of. These arguments about the ‘downstream’ use of titanium dioxide have been taken up by various industries, including the aluminium sector, whose bauxite residue or ‘red mud’ can contain high levels of titanium dioxide, SidenoteDocuments 6 and 7 in this batch and the paint industry. SidenoteDocument 18 in this batch

Of course, to state the obvious, if products do in fact contain suspected carcinogens like titanium dioxide, it is surely right that they be considered unsuitable for recycling, and should be disposed of properly and safely, so as to protect workers and local communities.

Baskut Tuncak, the UN’s Special Rapporteur with responsibility for the “implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes” could be expected to have strong views on waste management, and indeed he has told the Commission that the classification of titanium dioxide should be as robust as possible. He has expressed concern that the Commission’s weaker proposal will result in “withholding from workers, consumers, and the public at large, information concerning titanium dioxide’s suspected carcinogenic properties [which] would deprive them of essential information that is their human right.”

I am deeply concerned by the alleged failure of certain business interests, including the Titanium Dioxide Manufacturers Association (TDMA) to fully respect human rights in their products

Tellingly, Tuncak also calls out industry for its irresponsible behaviour on the issue: “Noting the responsibility of the private sector to respect human rights, I am deeply concerned by the alleged failure of certain business interests, including the Titanium Dioxide Manufacturers Association (TDMA) and its members, to fully respect human rights in their products and various activities implicating the hazards and risks of titanium dioxide.”

Despite this, TDMA and allies are clinging to their waste-related arguments even though, in the Commission’s own words, “downstream legal or socio-economic considerations are not part of [this] process”, which should instead be considered via other legislation. SidenoteDocument 4 in this batch

Divert, delay, weaken

Industry’s broad preference is for titanium dioxide to be completely removed from the present classification process. More recently, and off the back of a German Government proposal, it supports the idea of diverting the regulation of titanium dioxide into an alternative process run by DG Employment, whose aim is to develop “occupation exposure levels” (OELs) for workplaces. German industry has been vocal in supporting this idea, including the German paint and ink industry, SidenoteDocument 5 in this batch and the German chemicals industry, SidenoteDocument 6 in this batch with TDMA members SidenoteDocument 2 in this batch and CEFIC SidenoteDocuments 1 and 2 in this batch providing additional support.

But this OEL process would be far from adequate. As a measure which is aimed only at workplaces, it would not have any impact on consumers and self-employed people. Moreover, currently there is no way to be sure from a scientific point of view that a safe exposure value can be set for titanium dioxide.

Meanwhile previous research by Corporate Europe Observatory has shown how effective industry has been at lobbying and influencing the OEL process, successfully keeping chemicals off the list of those to be regulated, or ensuring that the exposure levels set are as weak as possible. Industry recommendations for exposure levels via the OEL process have, unsurprisingly, been consistently weaker than those proposed by trade unions.

No wonder industry would like to shift titanium dioxide to this other decision-making process; it would delay action for years, and the outcome would be far weaker. On the other side of the argument, the European Trade Union Confederation SidenoteDocument 12 in this batch along with the European Environmental Bureau of green NGOs, SidenoteDocuments 13 and 14 in this batch support keeping the chemical in the current process, with a robust classification based on the European Chemicals Agency’s recommendation.

Another proposal by two countries with a significant titanium dioxide industry (Slovenia and the UK) would avoid any labelling at all, but instead would see a ‘flag’ in the shape of a “note W” to inform about the particular toxicity of titanium dioxide. Many industry bodies have championed this proposal (including the Downstream Users of Chemicals Coordination Group, which includes 11 industry bodies, SidenoteDocument 10 in this batch as it would involve minimal changes to business-as-usual.

In the name of free trade

A final, discernible corporate tactic has been mobilising the titanium dioxide industry beyond the EU in the name of free trade.

Various US trade associations have submitted a brief to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) arguing that the proposed EU titanium dioxide classification “could unnecessarily constrain or even eliminate certain products from international trade”. When the Commission notified its titanium dioxide proposal to the WTO in December 2018, it received a further round of lobbying missives from overseas industry including US and Japanese trade associations SidenoteDocuments 3, 4, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17 in this batch. The Speciality Steel Industry of North America (SSINA) also submitted a position paper to the Commission SidenoteDocuments 5 and 8 in this batch drafted by lobbying law firm Kelley, Drye and Warren LLP, objecting to the classification.

The US Trade Representative has also recently called on the EU to postpone its classification proposal, arguing that it may be “unnecessarily disruptive to billions of dollars of US-EU trade”, while the “US mission” in Brussels has attended important EU meetings where titanium dioxide has been discussed. SidenoteDocument 11 in this batch

E171: another titanium dioxide lobby battle opens up

In April 2019 France announced its intention to ban the food colourant E171 (titanium dioxide’s food additive name) from all foodstuffs by 2020, because of the risks to human health from ingesting it. This plan has been notified to the Commission, and member states are presently discussing (via the Standing Committee on Plants, Animals, Food and Feed comitology committee) how to respond. Their options include: allowing France’s move to go ahead; adopting France’s position at the pan-EU level; or challenging France’s decision. It is clear what industry wants: “We are concerned that this suspension will result in fragmentation and disruption of the European Single Market while the weight of scientific evidence does not show any immediate issue”. This reaction by the TDMA indicates a common industry response to member state governments that try to ban particular products (see also, for example, the industry reaction to the proposed ban on specific single use plastic items), namely ‘you can’t do that because it will damage our profit-making within the EU and beyond’. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has previously ruled E171 to be safe as a food additive, although a French TV documentary has critiqued EFSA’s decision-making. A follow-up EFSA study on E171 is underway and has been seeking “additional clarifications” from industry before the final assessment can go ahead.

Member states divided, industry united

Industry is running an intensive lobby battle against the classification of titanium dioxide as a suspected carcinogen, and it is attempting to both reframe the debate and shift it to weaker decision-making processes.

Member states remain divided on how to handle titanium dioxide. Some support the original ECHA proposal for a comprehensive classification; some support the Commission’s weak proposal with the exemption for mixtures; and others support the German proposal for the alternative OEL process, or the Slovenian/ UK proposal to simply ‘flag’ its toxicity.

The REACH comitology committee remains in deadlock, with no sign of a break-through after many discussions, so the Commission has now proposed that a decision is made via a fast-track ‘delegated act’ procedure, which allows the Commission and its college of Commissioners to make the final decision. It would be advised during this process by an expert group called CARACAL, but while formal membership of this group is restricted to member state officials, attendance at (open) meetings can include a wider range of observers. For example in a June 2018 open meeting of CARACAL which included discussion on titanium dioxide, at least 13 industry bodies were present, but only 3 NGOs, and industry was able to present at least some of its demands. SidenoteDocument 11 in this batch Under the new delegated act procedure, once the Commission agrees to a proposal advised by CARACAL, the European Parliament (which is generally more open to arguments about human health and the environment) and the Council of the EU can reject the legislation, but cannot amend it.

Arguably the decision on titanium dioxide could set a precedent for chemicals with similar, harmful properties and the stakes are high. Concerns about public health, and workers’ rights, backed by science and the law, are in danger of being sacrificed to red herring distractions raised by industry - including costs, ‘over-regulation’, and free trade. And with the Commission looking to fast-track the decision on titanium dioxide, there is a major risk that the significant resources of the corporate lobby will enable industry to secure a win, leaving European workers and the general public without the full knowledge that different forms of titanium dioxide are suspected of causing cancer.